Motivation in students

Motivation is a phenomenon which has been investigated extensively by both psychologists and educational researchers. Motivation is related to the time students spend on their education (Berliner, 1990) and the level in which students regulate their own learning process. Time on task and self-regulation are subsequently related to how and how much students learn.

Definition and indicators

There are many different definitions of motivation. Schunk, Pintrich and Meese (2008) summarise it as follows: motivation is “a process in a goal-oriented activity which is started and maintained”:

- a process because motivation cannot be observed directly but must be deduced from activities such as task choice, effort, and persistence;

- goal-oriented because an (implicit) goal is the cause for the activity and determines the direction of it;

- activity because realisation of goals requires mental or physical activity;

- started and maintained because even though taking the first step can be difficult, maintaining an activity determines whether goals such as passing for a course or finishing a programme will be realised.

Schunk et al. (2008) also list several indicators for motivation:

- task choice when a task can be freely chosen;

- effort and persistence, specifically when faced with a difficult task;

- performance. This is an indirect measure for motivation as effort and persistence lead to better results.

Motivation in higher education

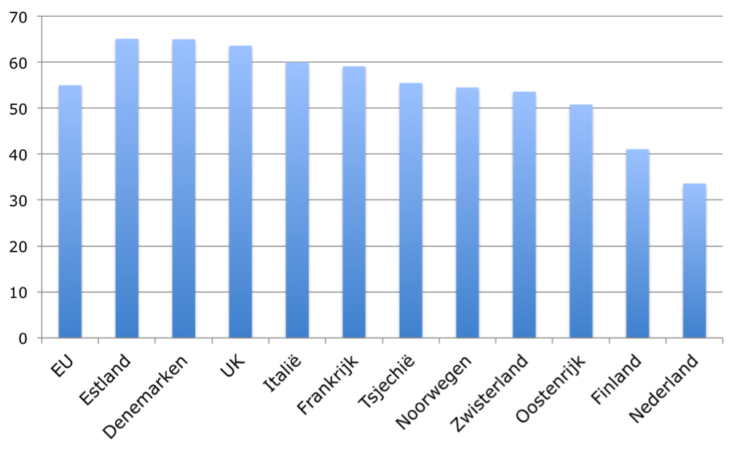

In comparative European research in the period of 2001 to 2005 alumni were asked several questions about motivation. The 70.000 alumni from different European countries had graduated in 2000. In figure 1 you can see the percentage of alumni that answered positively to the question whether they strived to attain the highest mark possible. Dutch students scored lowest out of all European Alumni.

Figuur 1. Percentage alumni 2000 who indicated to strive for the highest possible mark (Brennan, Patel, Wang, 2009).

Dutch alumni also scored lowest in the percentage of students who indicated to spend more than 40 hours per week on their studies. It is difficult to determine exactly what causes those low percentages. The European research also shows that Dutch alumni more often had work experience not related to their studies in comparison to other European alumni (Allen, Coenen & van der Velden, 2007).

This data shows that there is much to be gained when it comes to motivation.

Theories on motivation

In the first half of the previous century behavioural theories were dominant in research into motivation. The core of these theories is that positive behaviour can be reinforced by providing rewards and negative behaviour can be changed by providing punishment. The process of conditioning leads to association of certain behaviour with certain positive or negative reactions.

- Compliments and high marks stimulate students to work hard

- Consequences for being late in class (unwanted behaviour) leads to them be on time the next class.

When students get a low mark (a negative stimulus) when they have worked hard, their motivation can be negatively affected and as such their future performance.

The Cognitive Dissonance theory (Festinger, 1957) was very influential in the fifties and sixties of the previous century. The core of this theory was that people strive for consistence between their different cognitions, attitudes, and behaviour.

- When someone gets a low mark for, for instance, statistics, and – like most people – value a positive self-image, this could lead to a negative change in attitude towards that subject which in turn influences motivation.

In Expectancy-Value Theory (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000) the focus is the relationship between on the one hand motivation and on the other hand expectations students have on their own ability and the value of reaching the desired result. When people have low expectations of their chance of success and ascribe this partially or entirely to their own ability, they will value the result less. The cultural and social environment of the student influences the assessment of their own ability and the value that is ascribed to the result.

A distinction is made between the value ascribed to their self-image, the value ascribed to achieving subsequent goals (such as a career), the “costs” connected to a task, and the intrinsic value (the joy that working on the task brings).

- Success-experiences stimulate the perception of ability and thus motivation.

- Low grades and feedback directed at the person (“You can’t do this”) decreases the perception of ability and thus motivation

- Tasks should not be too easy, but also not too hard

- When students understand why tasks are important or why certain subject matter is relevant, it positively affects motivation.

- When students understand that being able to do something is largely something you develop, it stimulates their motivation to work on it.

- ‘First generation’ students, whose environment is not accustomed to the university, are at an extra risk of underestimating their ability.

- Culturally bound stereotypes play a role in the value that they ascribe to study results in general and results to specific subjects.

In the Self Determination Theory, which guides a lot of recent research on motivation, the premise is that satisfying human basic needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competency form the basis of motivation (Deci & Ryan, 2000). For instance, when a task is not challenging enough, does not leave enough space for your own expression, and is not executed in relation to others to whom the individual would like to connect, this task will not be considered motivating.

The consequences of this are far reaching:

A reward has a negative effect on autonomy and thus intrinsic motivation. In comparative literature studies on effects of reward on intrinsic motivation, a distinction was made between self-reported motivation and motivation measured by free choice to continue the task after having received a reward (Deci & Ryan (2000)). It is striking that an expected reward does not motivate people. An expected result that varies with the achieved result (i.e. a six when it is a ‘passing’ mark) has large negative effects on motivation. See also TED talk by Dan Pink.

When students value the group with which they study and have good relationship with their teachers, this has positive effects on their motivation because of the relatedness that comes with it (Tinto, 1999). As such, studying and in study groups has positive effects on motivation. Feedback of a lecturer with whom the students have a connection has positive effects on motivation, whereas feedback from a lecturer with whom there is no connection is more likely to be construed as , which has a negative effect on motivation (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Perception of own competence is a task contributes to the motivation for the task (see also the description of the expectancy value ).

Sources

- Berliner, D. C. (1990). What’s all the fuss about instructional time? In M. Ben-Peretz & R. Bromme (Eds.), The nature of time in schools: Theoretical concepts, practitioner perception (pp. 3-35). New York: Teachers College Press.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78. http://ovidsp.tx.ovid.com.proxy.library.uu.nl/sp-3.6.0b/ovidweb.cgi

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Pintrich, P. R. (1999). The role of motivation in promoting and sustaining self-regulated learning.International Journal of Educational Research, 31(6), 459-470. doi: 10.1n16/S0883-0355(99)00015-4

- Schunk, D. H., Pintrich, P. R., & Meece, J. L. (2008). Motivation in education: Theory, research, and applications (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. (Page 4)