Improving your students’ academic output: make your students information literate

Maak je studenten informatievaardig, NL

Are your students googling their entire research question when searching for literature? Do you want your students to use relevant sources instead of an obscure website? Do you want to prevent them blindly citing another article, or ensure they do not forget to add their bibliography? Learning and teaching information literacy skills in the proper way benefits you and your students.

What are information literacy skills?

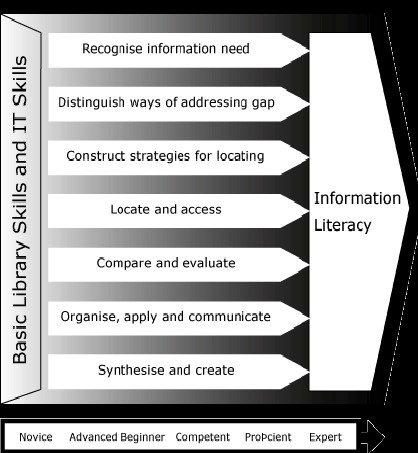

Figuur-1: SCONUL seven pillars model voor informatievaardigheden (1)

Information literacy skills include the knowledge, skills and attitudes required to find, select, evaluate, organise, process, use and publish information (1-5). In academia, information is often understood as scientific or academic literature or data. However, also information from other sources, such as newspapers, tweets or artwork can be relevant for research. Information literacy skills then serve as an umbrella term including media, digital and data literacy as well (1, 4).

.

Why?

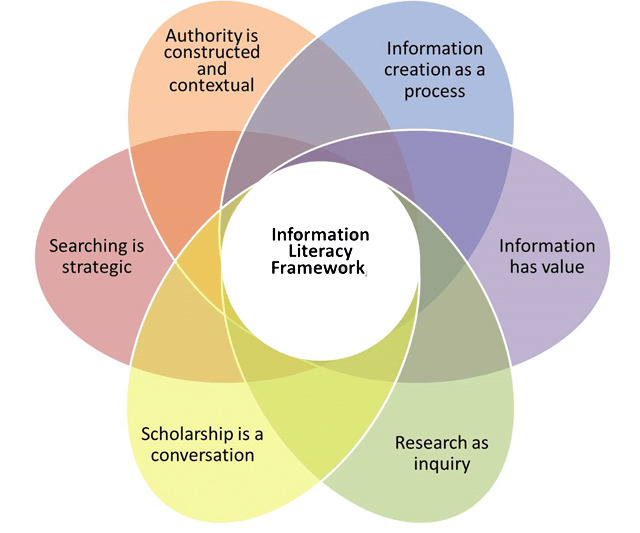

Figuur 2: Treshold concepts die de basis vormen van het ACRL framework voor information literacy (4) bieden een opening naar meer kennis en kunde binnen je eigen discipline.

How?

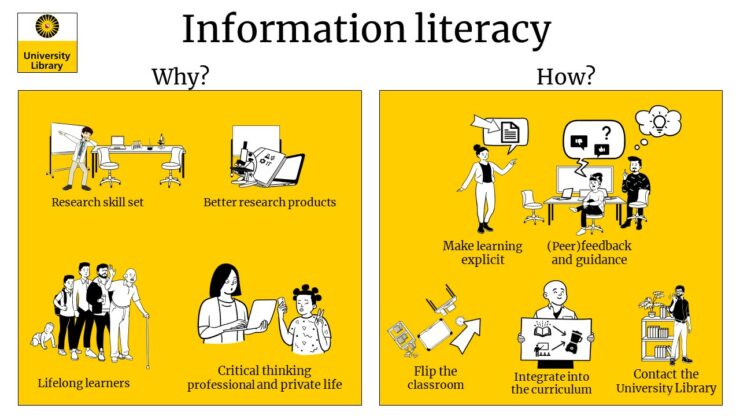

Save time: Ask the University Library to help you! The University Library offers a wide range of online training modules, libguides and services that help you incorporate information literacy skills into your curriculum and to make them an explicit part of it. For example: flip your classroom with the online training module Compass. Students finish the module with basic information literacy knowledge before class, which allows room to practice and reflect on information literacy skills during class. Compass consists of four separate modules that collectively practice the basics of information literacy skills. These are the four modules: Each of these modules can also be incorporated independently into your teaching. This ensures that the appropriate skills are practiced at the appropriate moment. In addition to these widely applicable Compass modules, there are two more specific Compass+ modules: Historical sources and Systematically searching for literature. In the module Historical sources students learn to identify which historical sources are required for their research, and how to find, access and use these sources. Systematically searching for literature helps students set up and carry out a systematic search for literature, for instance when performing a systematic review. All Compass and Compass+ modules can be accessed by students on the ULearning platform through their Solis-id. When these modules are completed successfully, students obtain a badge. Badges make students’ learning more visible and make it possible for them to demonstrate their acquired knowledge and skills. Another way to elevate information literacy training is to ask one of the library’s information or subject specialists to join your class to help your students in acquiring and deepening their information literacy skills. The specialist’s knowledge and competencies on searching, evaluating, and using information, as well as their expertise on open science, can be an eye-opener for students, helping them reflect on the process of finding and using information (2, 8, 15). The University Library cannot only help you and your students when searching for literature, but also offers training and advice within the field of open science, research data management and digital humanities. In the Teaching and Learning Collection, examples of learning activities can be found in which the University Library’s training modules, libguides and services could be included into a classroom setting: Are you looking for other options or do you have more questions on how to incorporate information literacy skills into your education? Contact the University Library and ask for the possibilities.

Figure 3. Infographic about the importance of information literacy training courses and how to incorporate them in your teaching in the best way possible.

- Bent M, Stubbings R. The SCONUL Seven Pillars of Information Literacy: Core Model For Higher Education [Internet]. SCONUL; 2011 Apr [cited 2022 Oct 8]. Available from: https://www.sconul.ac.uk/sites/default/files/documents/

coremodel.pdf - Bruce CS. Informed Learning [Internet]. Chicago, IL, UNITED STATES: Association of College & Research Libraries; 2008 [cited 2022 Aug 4]. Available from: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uunl/detail.action?docID=5888833

- Van der Meer H., Post M. Taxonomie voor informatievaardigheid: Digitaal leermateriaal gezocht en gevonden. IP Vakblad voor informatieprofessionals. 2020 Aug;4.

- Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL). Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education [Internet]. Chicago, IL, UNITED STATES; 2015 [cited 2022 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/

content/issues/infolit/framework.pdf - SHN UKB werkgroep Inofrmation Literacy. Metaliteracy [Internet]. SHB werkgroep Information Literacy. [cited 2022 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.shb-online.nl/onderwijs/information-literacy/vakinhoud/

- Vitea. Vitae Researcher Development Framework (RDF) 2011 [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2022 Aug 1]. 23 p. Available from: www.vitae.ac.uk/rdf

- Mahmood K. Do People Overestimate Their Information Literacy Skills? A Systematic Review of Empirical Evidence on the Dunning-Kruger Effect. Commun Inf Lit [Internet]. 2016 Dec 29;10(2). Available from: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/

comminfolit/vol10/iss2/3 - Inzerilla T. Teaching faculty collaborating with academic librarians: Devoloping partnerships to embed Information literacy. In: Media and Information literacy in higher education: educating the educators. Chandos Publishing; 2016. p. 67–86.

- Bury S. Faculty attitudes, perceptions and experiences of information literacy: a study across multiple disciplines at York University, Canada. J Inf Lit. 2011 Jun;5(1):45–64.

- Morrison L. Faculty Motivations: An Exploratory Study of Motivational Factors of Faculty to Assist with Students’ Research Skills Development. Partnersh Can J Libr Inf Pract Res [Internet]. 2007 Dec 3 [cited 2022 Aug 11];2(2). Available from: https://journal.lib.uoguelph.ca/index.php/perj/article/view/295

- Mackey TP, Jacobson TE. Reframing Information Literacy as a Metaliteracy | Mackey | College & Research Libraries. 2017 Apr 25 [cited 2022 Aug 1]; Available from: https://crl.acrl.org/index.php/crl/article/view/16132

- Barnard A, Nash R, O ’Brien Michael. Information Literacy: Developing Lifelong Skills Through Nursing Education. J Nurs Educ. 2005 Nov;44(11):505–10.

- Shorten A, Wallace . C., Crookes PA. Developing information literacy: a key to evidence-based nursing. Int Nurs Rev. 2001;48(2):86–92.

- Todd RJ. Integrated Information Skills Instruction: Does It Make a Difference? Sch Libr Media Q. 1995;23(2):133–8.

- Stellwagen QH, Rowley KL, Otto J. Flip This Class: Maximizing Student Learning in Information Literacy Skills in the Composition Classroom through Instructor and Librarian Collaboration. J Libr Adm. 2022 Aug 18;0(0):1–22.

- Montiel-Overall P. A Theoretical Understanding of Teacher and Librarian Collaboration (TLC). Sch Libr Worldw. 2005;24–48.

- Rivera E. Using the Flipped Classroom Model in Your Library Instruction Course. Ref Libr. 2015 Jan 2;56(1):34–41.

- Kuhlthau CC. Seeking meaning: a process approach to library and information services [Internet]. 2nd ed. Westport, Conn.: Libraries Unlimited; 2004 [cited 2022 Aug 15]. xvii, 247 p. Available from: http://swbplus.bszbw.de/

bsz262326078inh.htm - Todd RJ. Information Literacy: Philosophy, Principles, and Practice. Sch Libr Worldw. 1995 Jan 1;54–68.